Binaural Hearing

Binaural hearing enables mammals to localize sound sources in their surroundings, distinguishing directions from left to right, front to back, and up to down. This ability is driven by auditory cues — both monaural and binaural — that provide information about the direction and distance of sound sources. The two primary binaural cues are the Interaural Time Difference (ITD) and the Interaural Level Difference (ILD), which allow the localization of sound sources along surfaces that are axisymmetric around the interaural axis, known as the Cones of Confusion. Monaural cues, primarily derived from the spectral content of sound, help resolve ambiguities and distinguish between different positions within a cone of confusion.

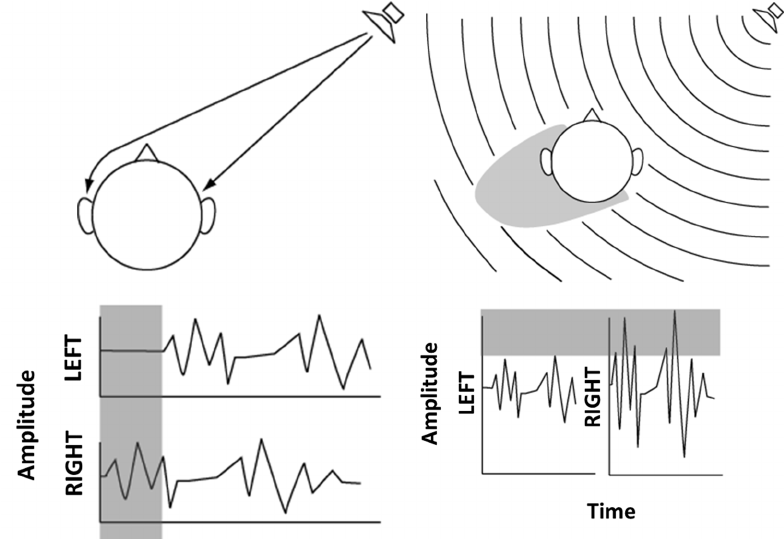

ITD refers to the difference in the time of arrival of a sound at the two ears and is most effective at low frequencies. For example, if a sound reaches the right ear before the left ear, it is obviously emitted from a source located in the right hemisphere. ILD refers to the difference in sound level between the ears and is most effective at high frequencies. For instance, at high frequencies, the sound reaching the right ear will exhibit a higher level than that reaching the left ear due to the shadowing effect of the head. The complementarity between these two primary binaural cues across the audible frequency range is known as the duplex theory, proposed by Lord Rayleigh in 1907.

However, ILD and ITD alone cannot resolve the ambiguity between source locations within a cone of confusion. For example, they may fail to differentiate between a frontal position and its counterpart in the back hemisphere, leading to a localization error commonly referred to as front-back confusion. Similarly, they cannot distinguish between sources located at the same azimuth (incoming angle in the horizontal plane) but at different elevations. To resolve these ambiguities, monaural cues, such as spectral content modifications caused by the shape of the outer ear, complement binaural cues and provide the necessary information.

Spectral modifications based on the source position result from the interaction of the sound field with the listener’s head and torso. For example, a sound originating from the back will have reduced high-frequency content compared to the same sound from the front hemisphere, due to the low-pass filtering effect caused by the back part of the outer ear (helix). Head rotational movements can also help resolve front-back confusion, as ITD and ILD cues dynamically change with the direction of head rotation relative to the source position. For elevated sources, reflections from the shoulders and parts of the outer ear (such as the antihelix, tragus, scapha, and concha) interfere with the direct sound, producing comb-filtering effects in the signal reaching the ears.

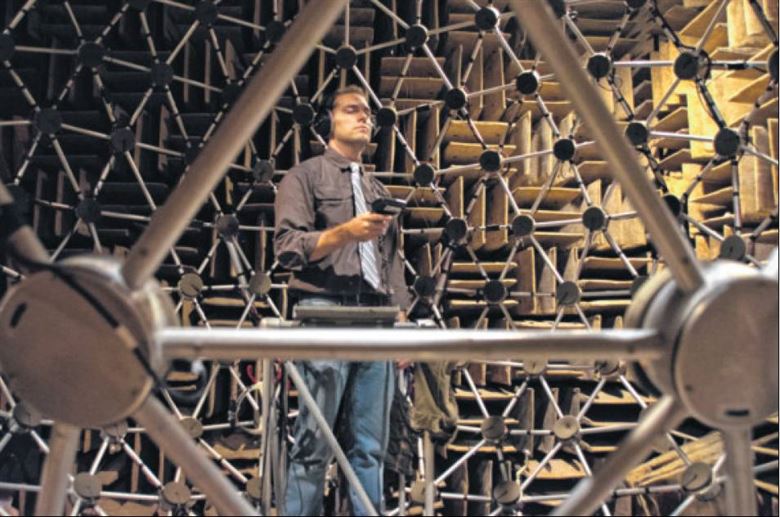

Monaural and binaural cues are encapsulated in spatial filters known as Head-Related Impulse Responses (HRIRs) or Head-Related Transfer Functions (HRTFs), which represent the transformation a sound undergoes as it travels from any location in space to the two ears. While HRIRs are measured in anechoic conditions, Binaural Room Impulse Responses (BRIRs) extend this concept to include measurements in echoic environments, accounting for the influence of the surrounding room. Both HRIRs and BRIRs can be used as convolution filters to apply to a dry sound, simulating a specific location of the sound source under anechoic and reverberant conditions, respectively. Moreover, they can be used to compute binaural decoders, based on various methods published in the literature, to render Ambisonic scenes of arbitrary complexity over headphones. Binaural reproduction can be achieved either statically (head-locked) or dynamically (head-tracked), if the listener’s head orientation can be monitored in real-time.

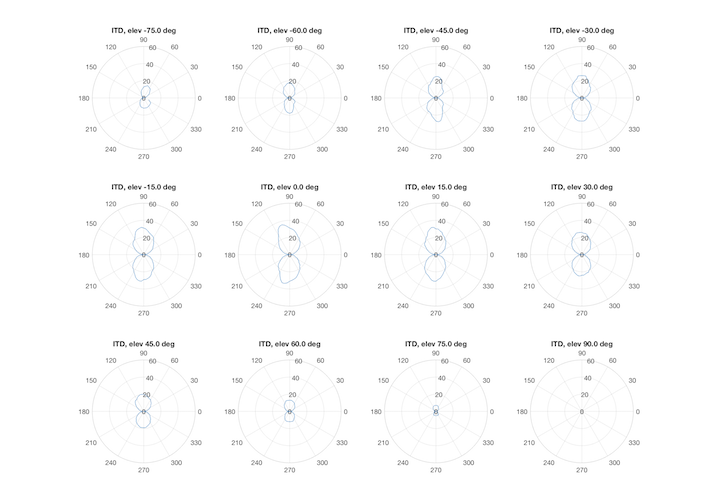

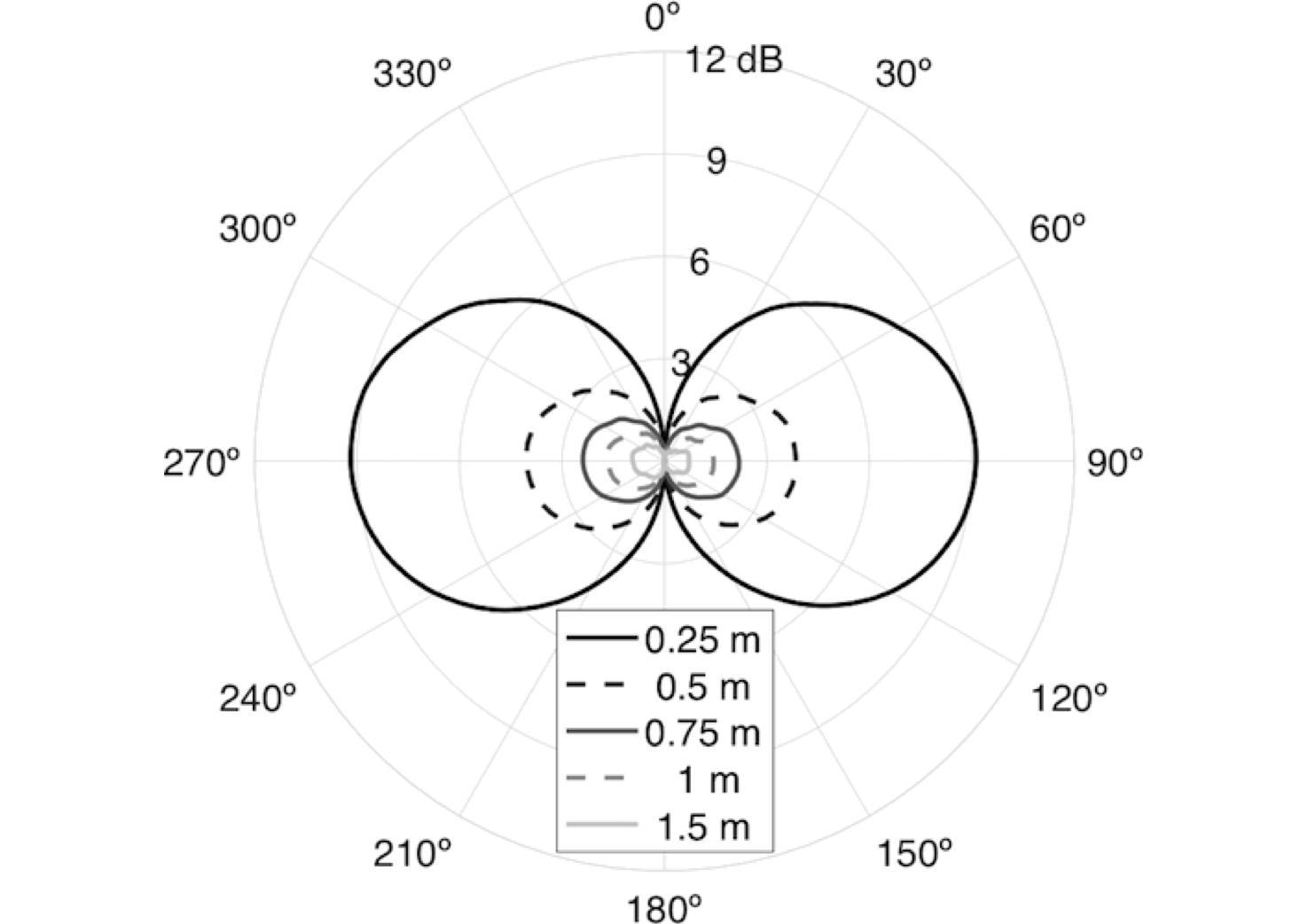

The computation of binaural decoders requires time-aligning each pair of HRIRs or BRIRs, which involves accurately estimating the ITD. Unlike HRIRs, some BRIRs may not exhibit their main peak when the direct sound reaches the ear but instead when a strong reflection arrives after bouncing off a reflective surface in the room. This is often the case for the contralateral BRIR (opposite ear) with lateral sound sources. An ITD estimation technique developed at Eurecat has demonstrated strong performance in these challenging cases, as shown in the above polar plots (ITD values are indicated in samples at a sampling rate of 48kHz).

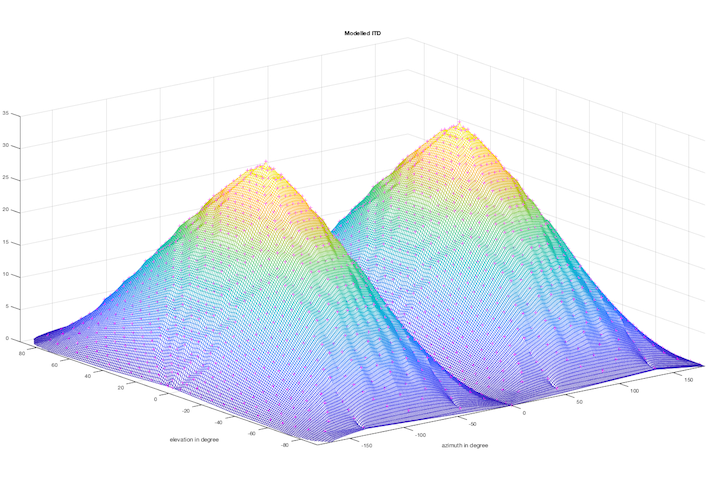

Another requirement for computing binaural decoders is the accurate modeling of ITD as a function of the source position (azimuth, elevation, and, to some extent, distance) and head circumference. At Eurecat, we developed a spherical head model that demonstrates highly accurate performance, as illustrated by the above plot (ITD values are shown in samples at a sampling rate of 48 kHz, as a function of azimuth and elevation for a source positioned at 2m).

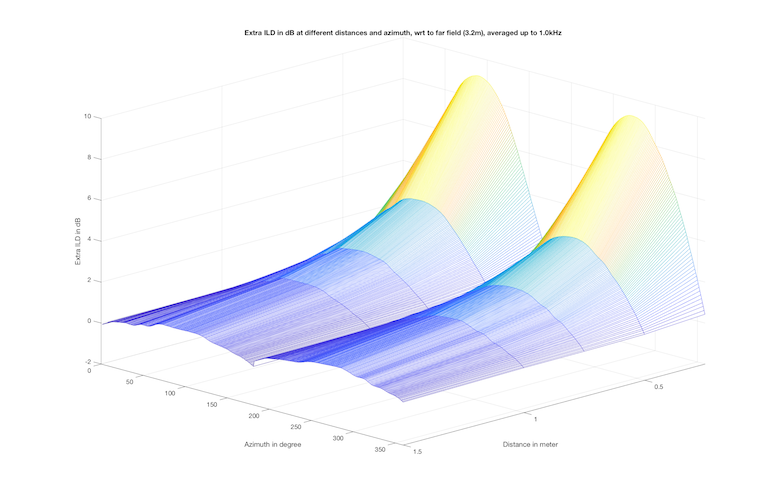

A final note on near-field effects: with a sound source in the far field — typically beyond about 1 meter — ILD and ITD are independent of the source distance and depend only on the azimuth and elevation angles. In contrast, for a source in the near field, binaural cues become distance-dependent. In particular, the ILD increases significantly as the source moves closer to the ear, as illustrated in the above plot for discrete distances and in the plot below as a continuous function of distance and azimuth angle. The unique behavior of binaural cues in the near field is a focus of research at Eurecat, aimed at modeling near-field HRIRs for reuse in auralization processes to simulate nearby sound sources.